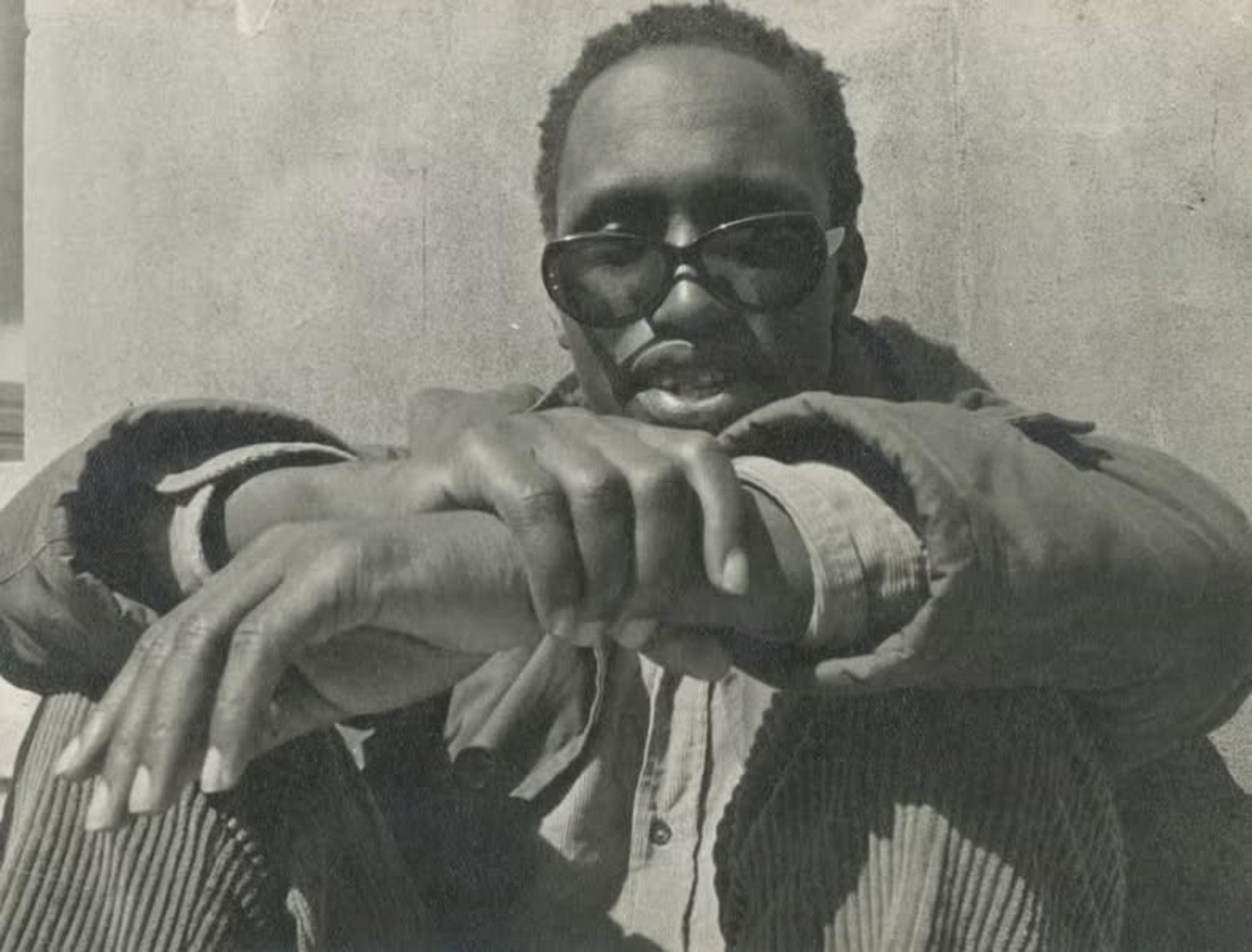

A Tribute to a Kenyan Philosopher

Image: Jonas Ekströmer/TT/IMAGO

-

Two men, one body.

I have always seen Ngugi wa Thiong’o not as a single writer, but as a man who lived two lives housed in one body. We have James Ngugi, the gifted English-language novelist, and Ngugi wa Thiong’o, the radical philosopher of language and liberation. With his passing on May 28th 2025, we are called to remember not just the man, but the transformation that defined his legacy.

Ngugi Wa Thiong’o was born in Kamirithu, in Limuru, a town located 29 kilometres away from Kenya’s capital, Nairobi City, to a large peasant family of about twenty-eight children. On the 5th of January 1938, the first Ngugi, James Githuka, the towering world-renowned East African writer and novelist, was born. His works were influenced by Africa’s colonial heritage, neocolonialism, and authoritarianism in post-colonial Africa. This man loved the English language, and while at Alliance High School, he would sing ‘God Save The Queen’ during parade time with his fellow schoolmates.

In 1957, while in Form 3A, going by the name J.T. Ngugi, he would write an article praising the white man’s religion, postulating that it was “without doubt the greatest civilising influence.” At this time, Dedan Kimathi is being executed at Kamiti Maximum Prison for leading an armed rebellion against the illegal British Empire in Kenya. Many years on, in August 2023, as Ngugi Wa Thiong’o reflected on the life of Micere Mugo, he writes how seeing Jomo Kenyatta surround himself with Anglophiles and colonial loyalists like Charles Njonjo made them both come up with the idea of writing a play about Dedan Kimathi.

The Alliance High School, Makerere University, and later Leeds University alumni studied English literature at his alma mater. To such, he became proficient in it and started writing great works of literature in the English language. Some of the notable works of this first Ngugi include: Weep Not Child (1964), The River Between (1965) – which happens to be his first book that I read while at primary school, and reads like an African Romeo and Juliet but engages with Kenya’s precolonial and colonial history, A Grain of Wheat (1967), and Petals of Blood (1977) – which attacked the new caste of political bourgeoisie in independent Kenya, and their continued exploitation of the Kenyan peasant. This is the last book he ever wrote in English. The book, coupled with the staging of his play “Ngaahika Ndeenda” (I will Marry When I Want), and his utterances against the Kenyatta and subsequently Moi regimes, saw him in and out of prison and ultimately led to his exile.

The second Ngugi, who we all know as Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, is a radical idealist. However, I tend to think of him as the most raw and thorough of African philosophers, especially regarding his views on language theory as an instrument for understanding the complexity of the effects of colonial hangovers in post-colonial Africa. This second Ngugi was born in the 70s, influenced by writers such as Frantz Fanon and Karl Marx, he would radically shift his penmanship to writing in the language of his ancestors, the Kikuyu language. This signified his paradigm shift from cultural nationalism towards revolutionary idealism. Regardless, all his books were in high demand worldwide and thus were translated into many different languages. Sure to his remarkability, he would win several prestigious literary awards every other week of his life, including his most recent, the Nabokov Award for Achievement in International Literature, an award named after the famous Russian-American novelist and poet, Vladimir Nabokov.

Ngugi’s philosophy is stipulated at great length in his 1986 treatise, Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature, where he displays his great genius in the English language, while showing us why he had to abandon it altogether. Here, he explores the intersections of politics, literature, culture, and African thought patterns in the post-colony which were shaped by the colonial language. He argues that the adoption of Western languages led to a disconnect between the African and his indigenous voice. If Dedan Kimathi is the gun-wielding general leading the Kenya Land and Freedom Army to restore Kenyan land to its rightful owners, here, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o wields a mightier weapon, the pen, to liberate the African’s mind from colonial subjugation using language.

To reclaim the Africans’ cultural integrity and resist the colonial cultural hegemony, he urges the African writer to think and write in African languages such as Kiswahili and Kikuyu. I recall my first time reading this work and marvelling at how he laid down his thoughts precisely and concisely. There, I knew that he was the African Ludwig Wittgenstein, and what I was reading was the African Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. However, just like the prophet who is never accepted in his hometown, I could not heed his teachings. After all, as a progeny of a people that had foregone their culture and language, I could not think or write in my mother tongue. Ludwig, right as always, would tell me how the limits of my language had limited the understanding of my world.

The language question.

The African literary scene began flourishing in the 1950s and 60s. This was towards the occident of European imperialism in Africa. As independent African countries emerged, writers such as Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka came up, and alongside them, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o stamped his name on Africa’s literary sphere. James Ngugi admired these two African writers. However, following the June 1962 writer’s convention in Kampala, Uganda, where he first brushed shoulders with the language question, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o would later fall out of love with the writers he had admired as a student.

Following the exclusion of African writers who wrote in African languages from the convention, such as the Swahili poet Shabaan Robert and the Nigerian writer Chief Fagunwa, he would then ponder deeply what African literature entailed. What defined it? Is it literature written by Africans? Or the setting of the story being in Africa? Or was the criterion language? If so, why were Fagunwa and Robert excluded? And what if a European wrote about Europe using an African language? Was that African literature? He was conflicted. In the convention, some writers present saw the use of European languages as having the capacity to unite Africans against divisive tendencies. Later on, he would state that colonialism is the birthplace of tribalism, the very thing that divides Africans.

The Nigerian critic Obi Wali believed that true African literature could only be written in African languages. He termed those written in English or any other colonial language a branch of European literature. Wali’s criticism planted a seed inside Ngugi’s mind. Ten years later, Achebe would deliver his speech on “the fatalistic logic of the unassailable position of English in our literature”, and that radicalised Ngugi against his role model. Their friendship would then sour when he called out Chinua Achebe on Decolonising the Mind. In his 2013 tribute to Chinua Achebe, he recalls his friendship with the literary giant and how people would confuse Ngugi for him or even Things Fall Apart for his first novel, Weep Not, Child.

The life of Ngugi wa Thiong’o, I would say, is woven into the very history of the Kenyan nation itself. His voice remained resilient at a time when silence meant an assurance of living, but he chose to be unsilent to save a young nation from corruption. He is the voice of reason in a generation where most people were not yet educated. Nonetheless, he ensured the seeds of the second liberation were planted in everyone’s mind by choosing to write in an indigenous language. Even though his country punished him for his brilliance, he remains a pillar of standing by what one believes in and fighting for it till the very end. He faced big men wielding guns and power using only a book and a pen, and to that I give him a big salute. As a young writer, for that alone, Ngugi wa Thiong’o looms large to me. On the philosophy of the language of African literature, I can never lace his boots. In his memory, may we never fall for the fatalistic logic of abandoning our mother tongues as Africans for someone else’s. Our tongues carry tomorrow's freedom. Aluta continua, Ngugi wa Thiong’o. Rest in peace.

Renny Kipkorir is an upcoming writer from Kericho County, Kenya. His works have been previously published in the first edition of Qwani: An Anthology, The Elephant, and The Kalahari Review. He is on Instagram as @rennycush and on X as @rennykipkorir.

Join Community

Step into Qwanis vibrant circle of creatives. Here, every voice matters, every story thrives, and camaraderie blooms. Become a part of our literary mosaic today!

Books on Amazon

Qwani Book One'© 2025 Qwani. All rights reserved. Designed by Qwani. Powered by Chari Designs